POETS Day! Richard Wilbur’s Tea with Sylvia and Mrs Plath

It would be a sad bit of trivia but for Wilbur’s poem.

We have a long weekend ahead with Martin Luther King Day on Monday. You may think, given the holiday, it would be greedy to call for a POETS Day. That’s what they want you to think.

Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday. You aren’t getting any work done on Friday afternoon before a regular weekend, much less a long one. The boss is probably halfway to his dacha as you read this. Get out, enjoy the sunshine, hit the bar, and claim the time that’s rightfully yours.

First, a little verse.

***

My favorite librarian recommended a moderate stack of books when I asked for essays attempting (essaying!) to define American poetry. As best I can explain, we’re known for our rebels. Pound wanted to make it new, Eliot stopped and restarted the world, Whitman sang to his own meter, Dickinson’s literary mentor loved her work but wasn’t sure it was even poetry. Robert Frost plays down-home, and Pound introduced him in a letter to Alice Corbin Henderson as “VURRY Amur’k’n,” but Frost was a wicked practitioner of conversational rhythms in a way that set him apart. William Carlos Williams made it his mission to set an American course, but he’s as unique as the rest of ‘em.

Strip away all the innovation. What’s the commonality we find in American verse that distinguishes it from European? Is there anything? My hunt may be an exercise in eye strain. Possibly Quixotic, but I enjoy the looking.

I’ve read more than a few definitive assertions “that American poetry can be defined by…” Some have been impressive, but none satisfactory. My librarian knows that and seems to have an able mental account of what raised my eyebrow or drew a scowl. The recent stack had a copy of Adam Kirsch’s 2008 collection, The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry. If you’re not familiar with Kirsch, he’s a poet whose verse I keep meaning to read more of, a critic whose essays I read often, and a professor who teaches at a place I was too dumb to get into.

The Modern Element offers twenty-five or so essays, most about a specific poet. Kirsch is not trying to posit an American poetic ethos but there are sift-able thoughts and pieces that might fit later, should a picture emerge. The book isn’t confined to American poets or poetry. In most of the essays, Kirsch finds something idiosyncratic about the subject poet, so further bulging the “unique” category when the poet is a Yank. And it may be that that’s the thread, but I’m too cautious to conclude American poetry is defined by individualism unless I’m really sure. Too obvious. Smacks of jingoism.

Kirsch pulls incidents into his criticism – builds around the incidents in some cases – that lend narrative to discussions of poetic merit or tendencies. James Merrill claimed to have turned to his Ouija board for inspiration, practically abdicating his claim as a poet in favor of serving as some sort of conduit through which spirits from beyond compose. That’s fairly common knowledge. Ephraim, a two-thousand-year-old Jew from whom the inspiration for Merrill’s The Book of Ephraim is delivered or transmitted, has been the stuff of criticism and speculation. Kirsch fleshes it out, lets us know that Merrill’s friend, the writer Alison Lurie, found Ephraim “foreign, frivolous, intermittently dishonest, selfishly sensual, and cheerfully coldly promiscuous.” I know that she knows (actually, I strongly assume that she knows but allow for New Age seriousness) that Ephraim was a persona, but I have a scene in mind now. More importantly, a friend told me what about the persona was not like the poet, what made it different, and now I have a better picture of what the poet was like.

The opening of his essay on Richard Wilbur gave a modest surprise. I’d never read Wilbur’s poem “Cottage Street, 1953” or heard the story behind it. Apparently, Wilbur’s mother-in-law was friends with Sylvia Plath’s mother. The young poet was fresh off her terrible Mademoiselle internship and the summer in New York she’d loosely fictionalize years later in her novel, The Bell Jar. She’d also just attempted to kill herself.

Wilbur describes the occasion for the tea (brief video here followed by a reading of the poem and commentary in a separate video clip from the same sitting.)

“My assignment when I went to the tea that day was to be encouraging to the very young Sylvia Plath about the life of the poet and to hearten her to set aside her suicidal urges and go on with her writing. That of course, was a very difficult assignment which I failed.”

Kirsch points out that the two poets were wildly dissimilar. He references two lines in Wilbur’s accounting, “Cottage Street, 1953” below: “Asks if we would prefer it weak or strong. / Will we have milk or lemon, she enquires?” Wilbur looked to beauty in the world where Plath was a torrent. He asks, “Does the fact that he was destined for happiness condemn his poetry to be weak, the tepid ‘milk’ to Plath’s acrid ‘lemon’?”1

The tea would be a bit of trivia but for Wilbur’s poem.

Cottage Street, 1953

Richard Wilbur (1921-2017)Framed in her phoenix fire-screen, Edna Ward

Bends to the tray of Canton, pouring tea

For frightened Mrs. Plath; then, turning toward

The pale, slumped daughter, and my wife, and me.Asks if we would prefer it weak or strong.

Will we have milk or lemon, she enquires?

The visit seems already strained and long.

Each in his turn, we tell her our desires.It is my office to exemplify

The published poet in his happiness,

Thus cheering Sylvia, who has wished to die;

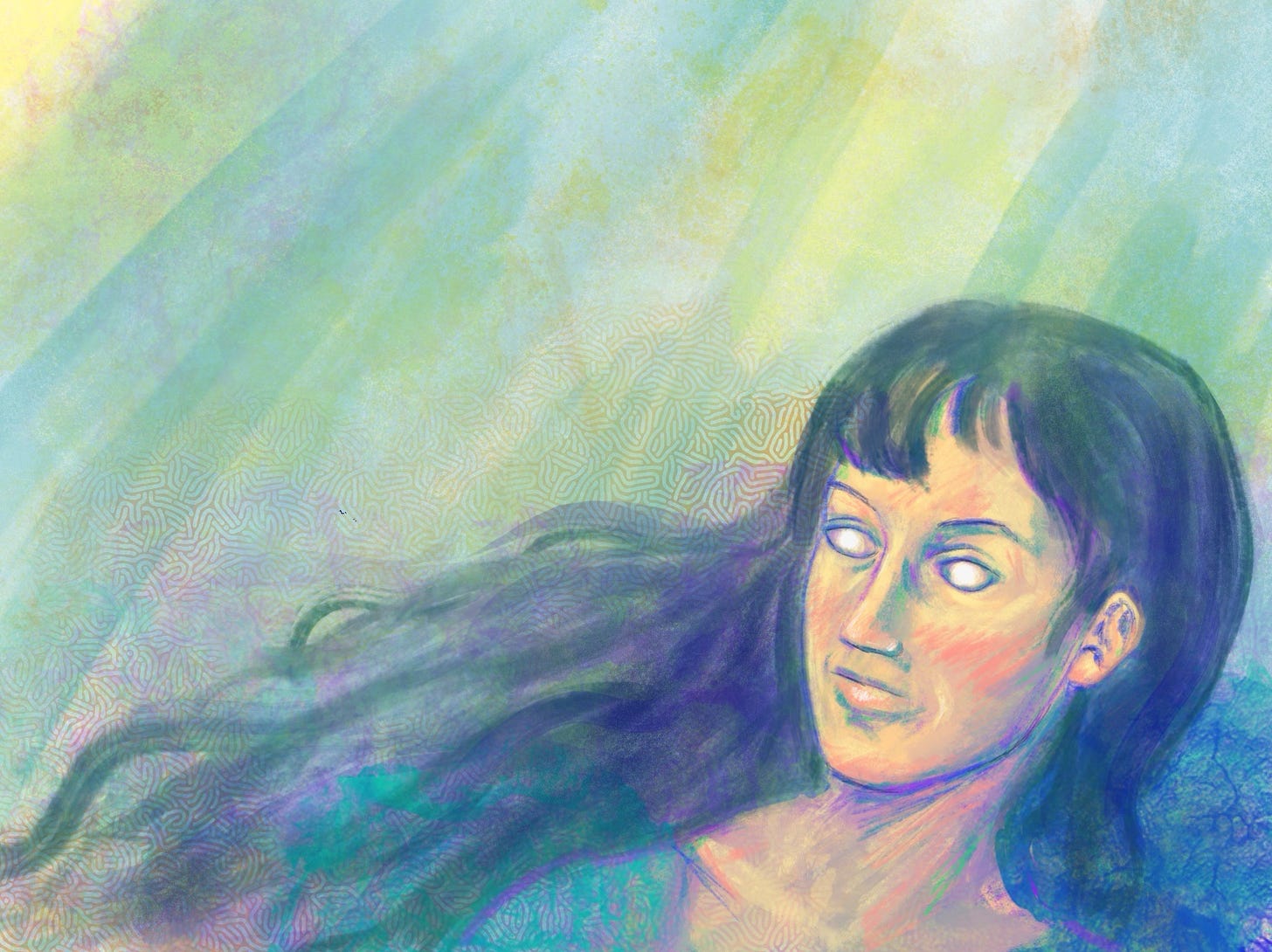

But half-ashamed, and impotent to bless.I am a stupid life-guard who has found,

Swept to his shallows by the tide, a girl

Who, far from shore, has been immensely drowned,

And stares through water now with eyes of pearl.How large is her refusal; and how slight

The genteel chat whereby we recommend

Life, of a summer afternoon, despite

The brewing dusk which hints that it may end.And Edna Ward shall die in fifteen years,

After her eight-and-eighty summers of

Such grace and courage as permit no tears,

The thin hand reaching out, the last word love.Outliving Sylvia who, condemned to live,

Shall study for a decade, as she must,

To state at last her brilliant negative

In poems free and helpless and unjust.

[This entry is cross posted at ordinary-times.com]

I spent years working as a sommelier. “Acidic” always refers to bright, sharp wines. “Lactic” means almost its opposite – fatty – even though lactic is a quality derived from lactic acid. Both are acidic. I fought the fight and lost. Maybe you’ve heard of me in some sad somm dirge, drifting from the dish room outward to the night.