POETS Day! Eliot’s Magi

Waiting for deliverance and searching for enlightenment share an end, but I don’t think Eliot likes that meta stuff.

I hope you get a gift so awesome it makes you feel like that time when you were a kid and Santa brought the big red shiny bike/doll house/basball mitt you always wanted. And I hope you have such a good time with friends and family that you forget all about whatever gift made you feel like that time you got the big red shiny bike/doll house/baseball mitt. And then the next day you get lost in a Christmas book and eat leftovers before a football nap.

It’s the best time of year. Cheers, and God bless.

***

I am the oldest of twenty-one cousins just on my mother’s side, so I get my fair share of Christmas cards. Shutterfly, Zazzle, and Adobe, to pull a few from a very long list, make it extraordinarily easy to send family portraits, family travelogue pictorial collages, and a funny one with room for the pets on the back of a decently weighted card stock. My grandfather was a dentist, and there’s something of his preventative ethic still in his great-grandchildren, aligned by height or posed in a teardrop around my cousins and their spouses, pearly whites beaming. We’re old enough that some of the great-grand-level kids tower over cousins I still consider babies. Add the same from my wife’s side, and there are enough wide-shouldered teen giants in the mix to put together a formidable 3-4 defense.

A favorite for years was the card from the Mitchells, a salt and pepper couple with two blond sons and a daughter who looks nothing like either parent. Maybe adopted, maybe a daughter-in-law from a shotgun type wedding? We had no idea. Until two years ago, we had no idea who they were but we’d get seasonal greeting from them every year: Mitchells at the Trevi Fountain, Mitchells at the Grand Canyon, Mitchells up to high jinx at a BAR BQ (“We’re like this all the time.”), posed and formal Mitchells in almost matching sweaters. They were the favorite card every year, the card that got center magnet on the fridge. My mother-in-law came by, saw the card, and asked how we knew “Bob and Veronica” or whatever their names are. He was her Merrill Lynch guy and must have picked our names along the way. That killed the mystery.

My dad was an attorney. As a kid, we’d get a treasured annual card from a well known—more notorious than respected—plaintiffs attorney every year. I thought we got one because we lived down the street from him. It turns out, he sent one to every member of the Alabama Bar Association. After a while, they were practically trading cards and definitely subject of conversation. He was a walking stereotype of a plaintiffs lawyer: hard drinking, ruddy faced, philandering, curly dyed hair, yellow Pantera driving, cigar chomper with a gravelly croak of a very loud voice.

The cards were a soap opera. One thing never changed. He was always central to the photo, wearing a tuxedo, and posed on the lawn of his great big gray stone castle1 which towered in the background. What made them the subject of Christmas cocktail gossip was the attending family. Who is the new wife? Where’s the son-in-law from last year? One Christmas he sent out a great big accordion card with all the previous ten or twelve years as retrospective. It was so convenient. Here’s when his second wife left him. The oldest daughter isn’t in 1989. Her father wasn’t speaking to her because she was stripping at Sammy’s. Here’s when he got remarried. Stripping again. It was a Cliff’s Notes Thornbirds comic strip in Walker Percy Southern Gothic.

One year it was just him with the St. Bernard.

Were I to give the title “King of all Christmas Cards,” I’d give it to Richard de la Mare. I’m certain there’s a Texas oil man sending diamond bedazzled Cadillacs or something equally ostentatious, but if we stick to cards as cards, de la Mare shines even among proud parents with impressive dental plans, wise investments gurus aiming to get you Trevi bound, and nouveau riche melodrama.

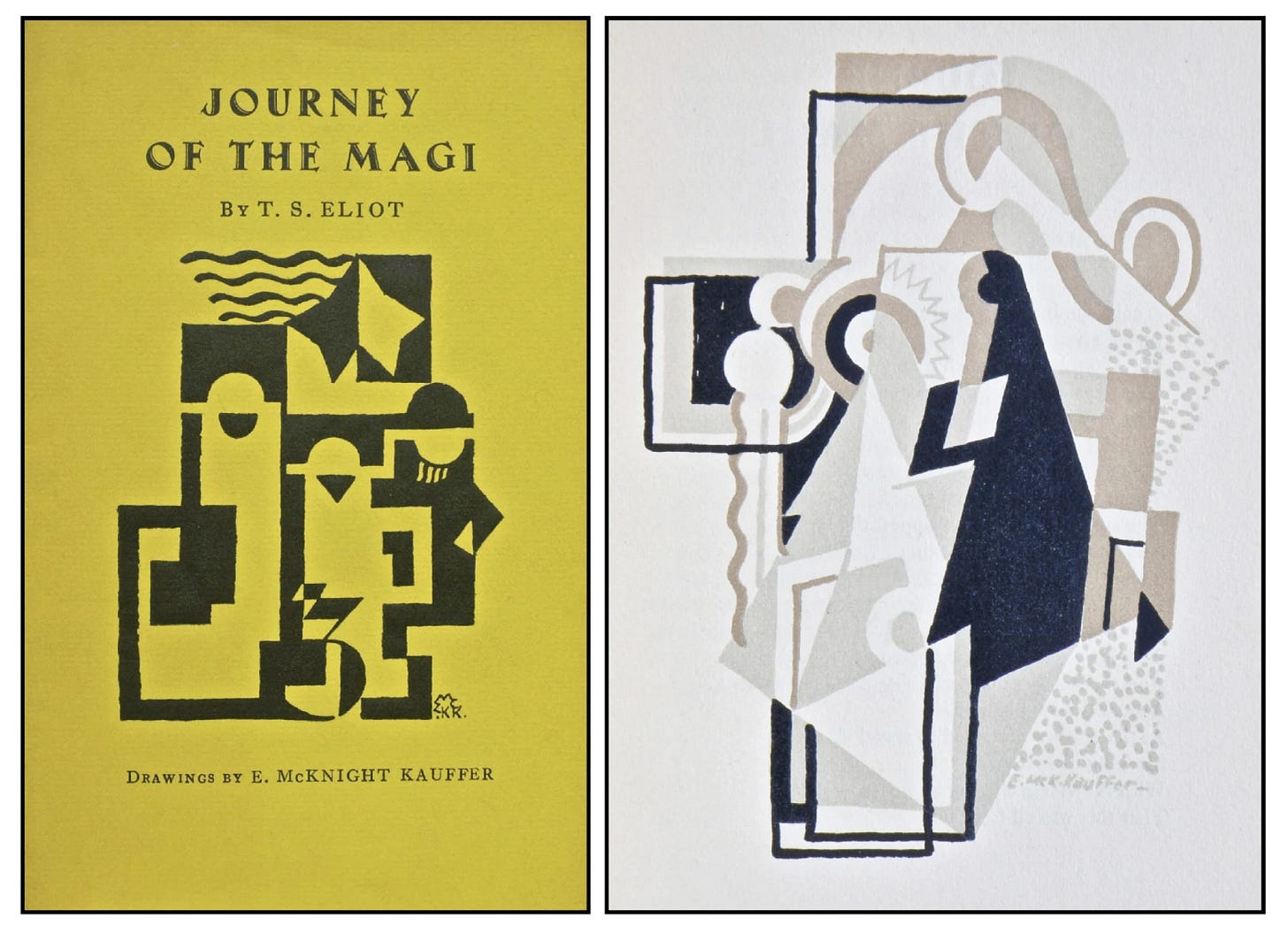

De la Mare was Faber and Gwyer (later Faber and Faber, and now plain old Faber) Publishing’s first production director. He wanted to send out an impressive Christmas greetings to clients, associates, prospectives, and friends of the company. He decided to send out a series of poems.

Richard de la Mare was the son of Walter de la Mare, the famous poet much loved and respected in literary circles at the time. Getting poets lined up was no problem. For starters, his father agreed to write one a year. He had the in as the son of a famous father, and Richard was an unapologetic name dropper who, this is from the Faber website, “never failed to make this connection clear in his letters to poets; and the tactic clearly worked.”

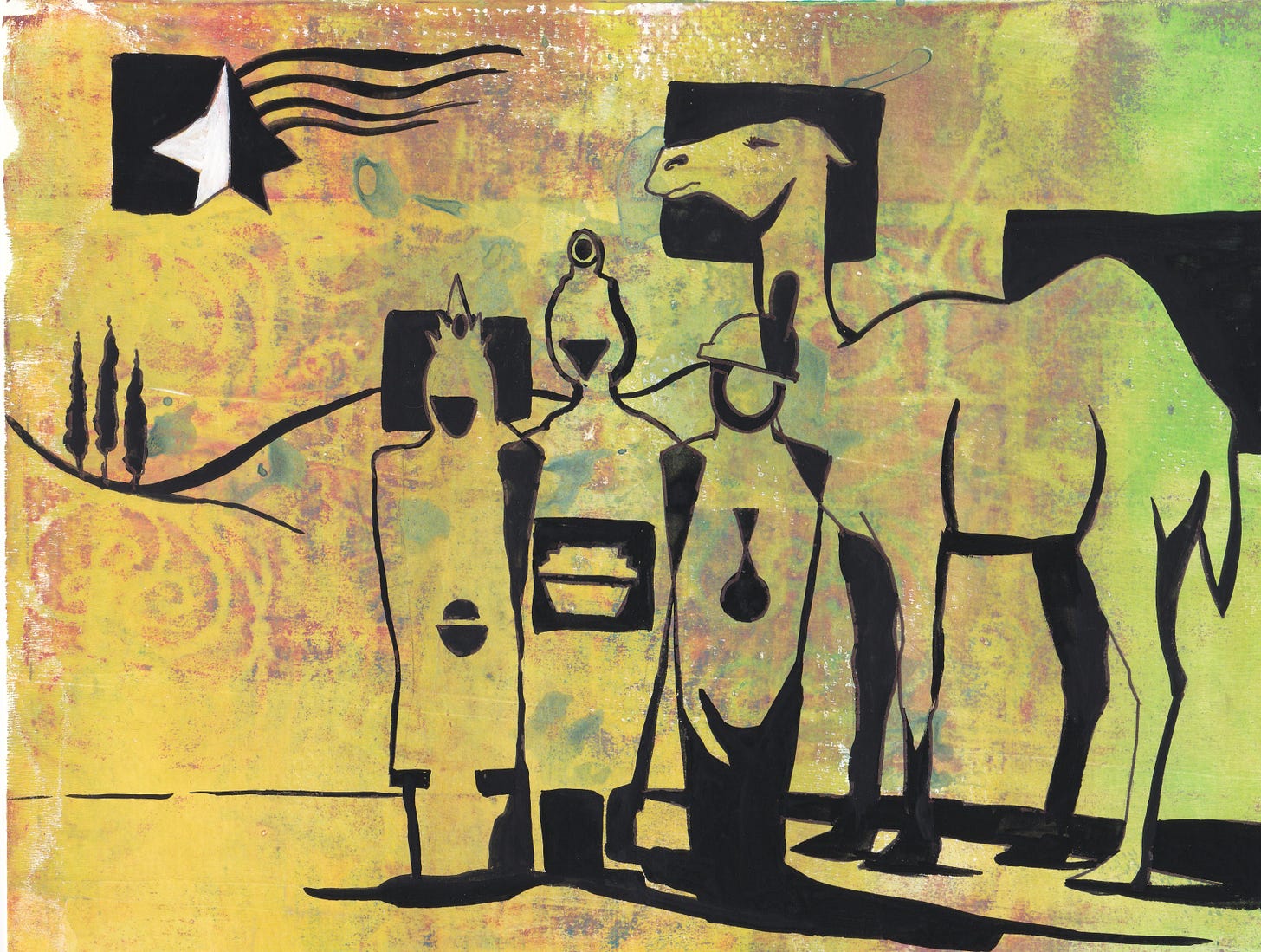

The series lasted from 1927 to 1931 and included works by G.K. Chesterton, D.H. Lawrence, Vita Sackville-West, Harold Monro, Siegfried Sassoon, Roy Campbell, Hilaire Belloc, and Edith Sitwell. Yeats did one, as did Thomas Hardy. Every year Faber and Gwyer or other Faber, as the times, published six or eight four page pamphlets, each with original art on the cover and front page with the final two pages taken up by a poem. The art was Richard’s passion. He pulled from avant garde disruptors, famous illustrators, and unknown “jobbers.” And Richard decided. For all the fame Yeats brought to the project, he had no say in what illustrations or paintings accompanied his verse. The sole exception was Belloc, who illustrated his own.

I don’t know if de la Mare picked who would get which or if distribution was random, but each recipient only got one poem. So in a year with poems from Hardy and Sackville-West, a printer might get W.H. Davies and a distributor Wilfred Gibson. I’m not sure of the allotments, but there were copies available to the public. I’ve read conflicting numbers, but there were roughly 2000-5000 copies printed depending on the year with an additional 100-500 limited editions signed by the author and numbered. How many of those went as gifts and how many to retail, I’ve no idea.

In 1925, T.S. Eliot left Lloyd’s bank to take a position as editor at Faber and Gwyer. I doubt Richard had to drop dad’s name to sign Eliot up, but I like imagining him popping into the next office with “Hi Tom. You may know me as plain old Richard, but did you know my dad is…” In any case, Eliot agreed to a poem a year. Below is his first, the 1927, contribution, “Journey of the Magi.”

De la Mare selected work by the poster artist, illustrator, and set designer Edward McKnight Kauffer as partner to Eliot’s first poem. Like Eliot, Kauffer was an American ex pat who spent most of his life in Great Britain.

Eliot had recently converted to Anglicism, or Anglo-Catholicism as he called the flavor that drew him. His narrator in the poem, an older man come to understanding as is not uncommon in Eliot, is grappling with the change ensured by the come Christ. It’s a perspective that reminds us of Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” just as seen from a different perspective. I think the perspective is more interesting considering Eliot’s recent conversion despite his famous insistence we leave the poet out of it and focus on the work. Rebirth, no matter how joyful, includes death. Hope includes uncertainty.

Waiting for deliverance and searching for enlightenment share an end, but again, I don’t think Eliot likes that meta stuff.

To describe the journey, Eliot borrows his opening, beginning with, per Wikipedia, “five lines adapted from a passage in the ‘Nativity Sermon’ preached by Lancelot Andrews, the Bishop of Winchester, before James I on Christmas Day 1622.”

From the text of the sermon:

“A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solsitio brumali, the very dead of winter.”

From that wilderness we are delivered.

Journey of the Magi

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins,

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Merry Christmas from me, my family, T.S. Eliot, Richard de la Mare, and the good people at Faber and whoever.

[This entry is cross posted at ordinary-times.com]

I make fun of that old plaintiff’s attorney because he was loud, uncouth, and cut a terrible fearsome figure. He was a tailor-made target for kids in search of a boogie man, but he was very nice. One summer the kids in our neighborhood spent our days shooting cap guns at each other in his yard. He had a stone bridge from his massive front patio over a depressed driveway. There was a rose garden on the other side, the perfect position from which to assault the Stormtrooper, Nazi or Star Wars depending on the day, held bridge from.

We made a hell of a noise playing around his house without permission. One day he emerged from the side door looking as cruel and vicious as ever, inching forward with accusing fingers. “Who wants lemonade,” he rasped.

We got cookies too.