POETS Day! “The Waste Land” Lees

The poem is dedicated to Ezra Pound with line “il miglior fabbro”: “the better craftsman.” That’s fawning. But...

I went on longer than I’d planned this week, so to the point without preamble: Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday. Get out of work. Run and be free. You’ve done your part, slaved the workweek throroughly enough. Escape the office and hit a happy hour, still sunlit park, catch a ball game, or ring up that attractive someone you’ve had a mind towards.

It’s POETS Day. Make the most of it.

But first, a little verse.

***

“I had thought of the Lycidas as a full-grown beauty—as springing up with all its parts absolute—till, in an evil hour, I was shown the original copy of it, together with the other minor poems of the author, in the library of Trinity, kept like some treasure to be proud of. I wish they had thrown them in the Cam, or sent them after the latter Cantos of Spenser, into the Irish Channel. How it staggered me to see the fine things in their ore! interlined corrected! as if their words were mortal, alterable, displaceable at pleasure! as if they might have been otherwise, and just as good! as if inspiration were made up of parts, and these fluctuating, successive, indifferent! I will never go into the workshop of any great artist again.”

– Charles Lamb, “Oxford in the Vacation”, kinda

I say “Kinda” because I’ve got lying eyes. I trust Cleanthe Brooks and Robert Penn Warren more than most. One of them wrote, in their coauthored classic Understanding Poetry, that Lamb wrote the above “in his essay ‘Oxford in the Vacation.’” The other one, no doubt, went over the final copy and approved. I read “Oxford in the Vacation,” and the quote was nowhere to be found. I ctrl F-ed it and tried to find “Lycides” on the page in case somehow a paragraph length distraction caused me to miss it. It wasn’t there.

Brooks or Warren was right, though, with the other also right but in an editorial capacity. I found an Atlantic article by Edmund Gosse in the May, 1900 issue, which the internet happened to have laying about. Gosse writes, “When Lamb came to read over these sentences, he was perhaps struck with their petulance, for they were omitted from the completed Essays of Elia [Lamb’s pen name] in 1823.” The original appeared in The London Magazine October 1820. It’s funny to me that a quotable quote about the mess of editing and rewriting was itself cut on consideration.

Were Lamb born a couple of centuries scant later, he’d wrestle with T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. I can’t say what opinion he’d have of the poem, only that he’d have one. The poem has been inescapable for those with poetic interests since its 1922 publication. What would he have made of The Waste Land, Centenary Edition in Full Color: A Facsimile & Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound from Liverwright, the original publisher of the poem in book form?

It’s one thing to read that Ezra Pound excised almost two thirds of Eliot’s manuscript, quite another to see reproductions of beige typewritten pages with pencil notes, slashes, suggestions sometimes themselves slashed and rewritten, and Pound’s querysome marginalia: “Vocative?” and “Vocative??”

There’s a very good talk by the poet Mark Ford and the Oxford lecturer Seamus Perry, and Ford may well also teach and Perry also write verse but that’s how they were presented to me, on The Waste Land where they discuss Pound’s input. Pound thought he midwifed the poem. Eliot was no doubt indebted to the man and pleased with all he’d done. The poem is dedicated to Pound with line “il miglior fabbro”: “the better craftsman.” That’s fawning. But to listen to Ford and Perry, Eliot thought Pound claimed too much credit. Probably, though that’s an expected outcome when dealing with Pound.

The Pound/Eliot correspondence of December, 1921, as found in The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound 1907-1941, is a fun read. Pound is direct—this stays, that goes, if you must then…—while flighty at the same. He peppers the letters with dialect and wisecracks but on the poetry and what should be done, he’s businesslike. After a run of corrections and suggestions he writes, “Complimenti, you bitch. I am wracked by seven jealousies,” and then throws in a twenty-five line poem about the project and aggrandizing his role. The following few lines give the gist.

from Sage Homme

Ezra Pound (1885-1972)If you must needs enquire

Know diligent Reader

That on each Occasion

Ezra performed the Caesarean Operation.

Eliot responds to Pound’s suggestions with either “O.K.” or further questions. He gives a mum “Complimenti appreciated, as have been excessively depressed,” and addresses Pound’s poem with “Wish to use the Caesarean Operation in italics in front.” No question mark. Pound responded to that with a throw-away in his next letter: “Do as you like about my obstetric effort.” The men were very different. Pound was a freewheeling showman while Eliot, as Virginia Woolf famously quipped (she always “quipped,” never “said,” per style guide, see also: PARKER, DOROTHY) “wears a four-piece suit,” but there’s Odd Couple comic chemistry.

Most fans of poetry are familiar with The Waste Land’s opening stanza.

The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Königssee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hafgarten,

And drank coffee, talking an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the archduke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, Hold on tight. And down we went.

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

It’s a bold statement. Eliot immediately connects to the beginnings of English language poetry with April to recall Chaucer’s “Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote.” It’s often said that there’s a prophetic voice followed by a woman called Marie, but I think it may all be Marie. In either case, we’re told about transformative spring and how she and others grew comfortable in winter, so much so that they missed spring entirely, surprised by summer when they go about their lives busying themselves with trivial things. Winter promised thrills, presumably rejuvenation, but they missed the Isis/Osiris period, finding a dull, repetitive season with no innovation, reading of the past and following an eternal summer’s latitude. Our poetry promised and then settled and we have stagnated. We lack spark, having squandered a period of fertility, and carry on as if content.

Eliot is a man who sees truths. There’s inevitability in him. He’s a fatherly figure, certain and professorial. That’s the image. I share a bit of Lamb’s horror at seeing the workshop. The Liverwright centenary edition tells the story of the making of The Waste Land in its introduction. Eliot was in a mess of a state throughout the writing and publishing process. We read of his 1919 struggling attempts to publish a volume of poetry, including “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” bundled with prose essays. He was worried about money, his and his wife Vivian’s health, and any hope of a literary future. Centenary Edition editor Valerie Eliot, who I assume wrote the introduction, quotes from a January 26, 1919 letter from Eliot to his New York agent, John Quinn.

“I am not at all proud of the book—the prose part consists of articles written under high pressure in the overworked, distracted existence of the last two years, and [is] very rough in form. But it is important to me that it should be published for private reasons. I am coming to America to visit my family sometime within the summer or autumn, and should particularly like to have it appear first. You see I settled over here in the face of strong family opposition, on the claim that I found the environment more favourable to the production of literature. This book is all I have to show for my claim—it would go toward making my parents contented with conditions and towards satisfying them that I have not made a mess of my life, as they are inclined to believe.”

The four-piece suit is nowhere in that letter. He follows up in a letter dated January, 26:

“…my father has died, but this does not weaken the need for the book at all—it really reinforces it—my mother is still alive…”

Eliot felt pressure to write another great poem after “Prufrock.” As early as 1916, he feared that he’d set expectations, his wife’s if not the public’s, too high with the success of that work. In 1919, he still hadn’t gotten around to doing so, telling Quinn he “hoped to” and his mother of his New Years resolution to get started. He didn’t though, not right away.

In October of ‘21 he took to the countryside and set up in Margate where he claimed to have written fifty usable lines. A month later he left for Lausanne, Switzerland in search of medical bliss from respected nerve man, Dr. Roger Vittoz. He wanted calm and focus.

In January, he was back in London to give Pound nineteen pages of manuscript.

The poem two years (at minimum) in the planning was written in a medically supervised flurry of creativity. He labored for ages and wrote in a flash of inspiration. Stream of consciousness with meticulously considered allusion. In any case, he knew it needed fixing and knew Pound was the man for the job.

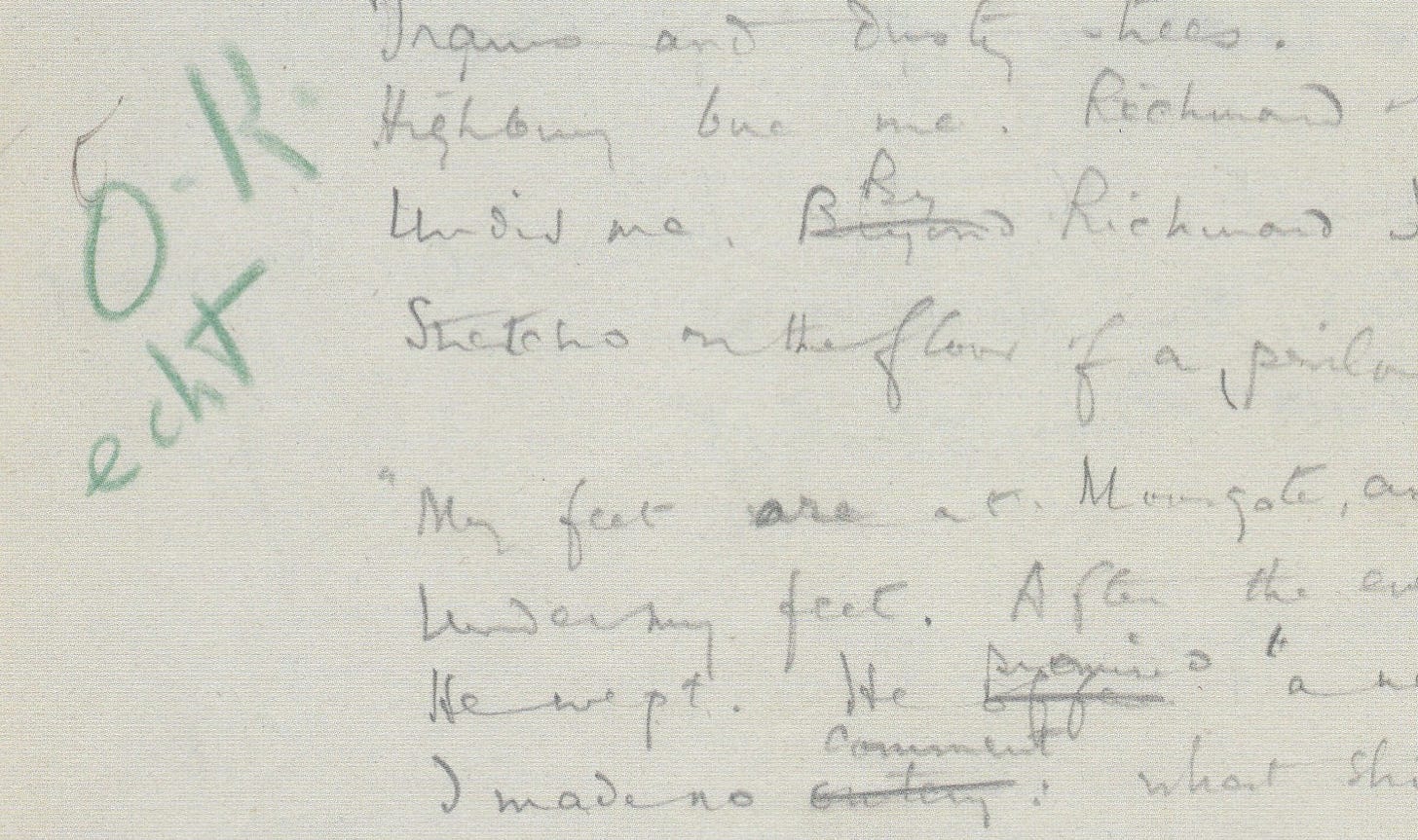

Ford and Perry speak to Pound’s grasp of Eliot’s aims, his recognition of what was essential. He was ruthlessness in striking chaff. “Echt,” meaning real, authentic, or true, peppers the margins. Pound’s scrawled “Echt” to the right of part III’s “A rat crept softly through the vegetation,” and with a line indicating the whole stanza, an green crayon “O.K. echt” to the left of “Highbury bore me. Richmond + Kew / Undid me,” later in the same part. Eliot wasn’t sure what he had. I have in my notes that he told someone—and I can’t seem to put my hands on who that someone is, so let’s say Richard Aldington because I’m pretty certain it was him— that he believed there were thirty good lines in the poem. Pound the Imagist treated the ethos of the poem directly, left absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

He struck the full page before “April,” but he didn’t seem to see the power, the boldness of “April” as the opening. There were “superfluities at the end,” he wrote. If you must keep ‘em, put ‘em at the beginning before the ‘April cruelest month.’” It was “Shantih, shantih, shantih,” as an ending he was certain of. The beginning, less so.

The fifty four lines that opened the draft told the story of a group of friend’s attempted mischief that comes to no consequence. To impress a a girl, one of the party kicks out at a drum during a concert but, “She never did take to me.” Steve ducks into a brothel but the motherly madam tells him he’s too drunk and feeds him breakfast. A cop catches them “committing a little nuisance” in a alley, but a well connected man gets them out of trouble, takes them to a club and they bet on a pointless running race. All efforts to go beyond what is generally acceptable thwarted, ignored, reined in, or subject to rescue; stymied innovation.

Pound struck all of that. Why show frustrated attempts to break from convention through anecdotes when with “April,” you have a bitter invocation of a spring that never came, upfront and direct. Echt.

The manuscript is scratched through, corrected, and annotated. Below is the typed, beneath the pencil and pen revisions, uncorrected text of the fifty-four lines intended to appear before “April…”

The Burial of the Dead

First we had a couple of feelers down at Tom’s place,

There was old Tom, boiled to the eyes, blind,

(Don’t you remember that time after a dance,

Top hats and all, we and Silk Hat Harry,

And old Tom took us behind, brought out a bottle of fizz,

With old Jane, Tom’s wife; and we got Joe to sing

“I’m proud of all the Irish blood that’s in me,

“There’s not a man can say a word agin me”).

Then we had dinner in good form, and a couple of Bengal lights.

When we got into the show, up in Row A,

I tried to put my foot in the drum and didn’t the girl squeal,

She never did take to me, a nice guy—but rough;

The next thing we were out in the street, Oh was it cold!

When will you be good? Blew into the Opera Exchange,

Sopped up some gin, sat in to the cork game,

Mr. Fay was there, singing “The Maid of the Mill”;

Then we thought we’d breeze along and take a walk.

Then we lost Steve.

(“I turned up an hour later down at Myrtle’s place.

What d’y’ mean, she says, at two o’clock in the morning,

I’m not in business here for guys like you;

We’ve only had a raid last week, I’ve been warned twice.

Sergeant, I said, I’ve kept a decent house for twenty years,

There’s three gents from the Buckingham Club upstairs now,

I’m going to retire and live on a farm, she says,

There’s no money in it now, what with the damage done,

And the reputation the place gets on account of a few bar-flies,

I’ve kept a clean house for twenty years, she says,

And the gents from the Buckingham Club know they’re safe here;

You was well introduced, but this is the last of you.

Get me a woman, I said; you’re too drunk, she said,

But she gave me a bed, and a bath, and ham and eggs,

And now you go get a shave, she said; I had a good laugh,

Myrtle was always a good sport”).

We’d just gone up the alley, a fly cop came along,

Looking for trouble; committing a nuisance, he said,

You come on to the station. I’m sorry, I said,

It’s no use being sorry, he said; let me get my hat, I said.

Well by a stroke of luck who came by but Mr. Donavan.

What’s this, officer. You’re new on this beat, aint you?

I thought so. You know who I am? Yes, I do,

Said the fresh cop, very peevish. Then let it alone,

These gents are particular friends of mine.

—Wasn’t it luck? Then we went to the German Club,

We and Mr. Donavan and his friend Joe Leahy,

Found it shut. I want to get home, said the cabman,

We all go the same way home, said Mr. Donavan,

Cheer up, Trixie and Stella; and put his foot through the window.

The next I know the old cab was hauled up on the avenue,

And the cabman and little Ben Levin the tailor,

The one who read George Meredith,

Were running a hundred yards on a bet,

And Mr. Donavan holding the watch.

So I got out to see the sunrise, and walked home.