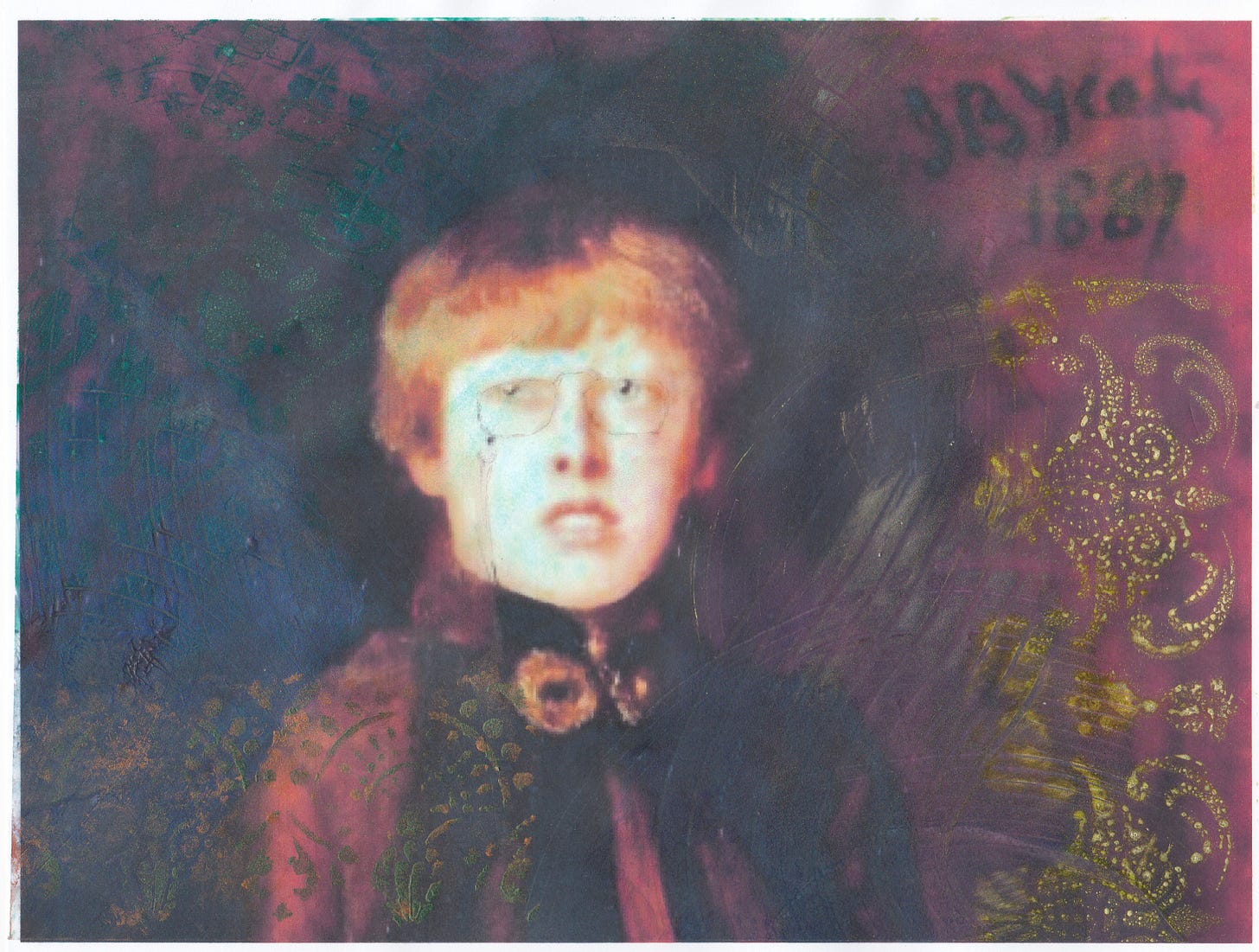

POETS Day! Katharine Tynan

I can't help but feel like she was so involved in the Irish cause because it was cool; that at a later date she would have been a woman Tom Hayden swore to Jane Fonda, "She's just a friend!"

Smoking looks cool. The converse is true as well. Not smoking is awkward. P.J. O’Rourke wrote, “People who don’t smoke have a terrible time finding something polite to do with their lips.” I’d say the same about their hands. Few have the Italian gift for gesturing. If there’s a desk level piece of furniture, maybe a chair back, leaning takes care of one hand. The other? I don’t know. Roll the Chapstick in your pocket? A lot of the cool people died so we bought gum and got snippy with waiters for a while. Now we’re awkward and have, on average, ten more years to kill.

In 1955, roughly 57% of American adults smoked. That number is just over 11% now. Over the course of seventy years, we have reduced the smoking share of the population by 46% points. “Non-smoking” offices became all the rage somwhere in the 80s. Everyday, 57% of the smoking workforce stepped out for a ten minute commiseration with other smokers. How many times? Twice? Three times a day? The Industrial Revolution. The Computer Revolution. New methods of management. We’ve heard myriad ways we’ve increased worker productivity but over seven back-loaded decades more than half the workforce stops taking thirty minutes a day off and we hear nothing. Something’s not right.

They don’t notice. Half of it’s make-work anyway. Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday. Start Friday afternoon a few hours before they tell you it’s okay. They really don’t notice.

First, a little verse.

***

“When Lionel Johnson and Katharine Tynan (as she was then), and I, myself, began to reform Irish poetry, we thought to keep unbroken the thread running up to Grattan which John O’Leary had put into our hands, though it might be our business to explore new paths of the labyrinth. We sought to make a more subtle rhythm, a more organic form, than that of the older Irish poets who wrote in English, but always to remember certain ardent ideas and high attitudes of mind which were the nation itself, to our belief, so far as a nation can be summarised in the intellect.”

– W.B. Yeats “Poetry and Tradition”

Yeats and Lionel Johnson were contemporary members of the Rhymers Club when Irish mythology and history was the talk, an association Yeats credited with deepening his interest and devotion to his home and its people. The two collaborated on Poetry and Ireland: Essays by W.B. Yeats and Lionel Johnson in 1908. It seems the two were friends, but it may have been that they shared a fascination and drive to preserve a vein from the literary past and develop its admiration that it would infuse future works.

Yeats is known as Yeats. His biography is well spread. Lionel Johnson would have gone down as an English poet with Irish sympathies and a frequent habit of bringing up his Irish ancestry but otherwise as a participant in a movement whose individuals scarcely escaped the shadow of Yeats. Instead, he introduced Lord Alfred Douglas to Oscar Wilde and became a footnote.

He was very angry at Wilde.

The Destroyer of a Soul

Lionel Johnson (1867-1902)I hate you with a necessary hate.

First, I sought patience: passionate was she:

My patience turned in very scorn of me,

That I should dare forgive a sin so great,

As this, through which I sit disconsolate;

Mourning for that live soul, I used to see;

Soul of a saint, whose friend I used to be:

Till you came by! a cold, corrupting, fate.Why come you now? You, whom I cannot cease

With pure and perfect hate to hate? Go, ring

The death-bell with a deep, triumphant toll!

Say you, my friend sits by me still? Ah, peace!

Call you this thing my friend? this nameless thing?

This living body, hiding its dead soul?

I have assumptions about Wilde’s demeanor and read attitude into his quips; assumptions refueled by by every theatrical performance depicting the man save, counter-intuitively, Stephen Fry’s. Of all the times I’ve seen someone play Wilde, Fry seemed the least dedicated to marrying wit with flouncy and contends with foppish as sufficient. In short, I have a hard time imagining that when Johnson introduced Lord Douglas to Wilde he thought he was joining straight with straight. Though there are people who maintain their grandmother was shocked when she found out about Liberace.

For Yeats’s purposes, Johnson was alluded to as a very talented man with noble literary goals. By Grattan he meant The Right Honourable Henry Gattan, Member of the Irish Parliament and brilliant orator in the cause of Irish independence. Edinburgh Review founder and salad dressing recipist, Sydney Smith said of Gattan, “He thought only of Ireland; lived for no other object; dedicated to her his beautiful fancy, his elegant wit, his manly courage, and all the splendour of his astonishing eloquence.” John O’Leary was a muscular separatist, convicted of treason, who spent his post prison years god-fathering various Fenian causes.

A quick search tells me that she wrote pot-boilers. I had no idea why she was mentioned in such company by Yeats.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography has a good article about Katharine Tynan Hinkson (as she was later). Words stick to people as their info gets copied and pasted around the internet so I’m not sure if the recurring “pot-boiler” description of her novels began with them or not, but Irish Biography claims “from 1895 to 1930 she wrote more than 102 pot-boilers.” I liked that line because implies scholars are torn as to her authorship of one or more other pot-boilers in a recently discovered folio. Quick hit novels were her trade.

Tynan met Yeats shortly after publication of her first book of poetry, Louise de la Vallière and Other Poems, in 1885. He was impressed and encouraging of her writing while solicitous of her opinion and input. Her help in curating works with Yeats and Johnson for Poems and ballads of Young Ireland (1888) I suspect is what “began to reform Irish poetry,” refers to. Yeats had a great deal of respect for her sensibility: “we – you and I – chiefly have made a change and brought into fashion in Ireland a less artless music.”

Yeats was smitten. One source says that he planned to ask for her hand. Most say that he “probably” did. I don’t know how much the “probably” comes from a source or because Yeats was a profligate proposer even if you restrict the count to Maud Gonne and family. There’s a peek at Yeats’s character in that he called her “Miss Tynan” until 1889. It’s tempting to say that’s more a peek at the propriety of the time, but propriety isn’t notable. He was an awkward guy.

The Miss stuff stopped around the time she’s said to have met Henry Hinkson in 1888. She and Hinkson would marry in 1893 and I can see a jealous Yeats tacking to familiarity in reaction to Hinkson’s arrival. The Hinksons married in London, where they took up residence. They kept in contact. I read that Yeats edited a collection of her poetry in 1906, Twenty-One Poems. She didn’t publish another non-potboiler until 1911’s New Poems. In 1920 Tynan sold her letters from Yeats for a hundred pounds. That ticked him off and signaled the end of their friendship.

Joining the Colours

Katharine Tynan (1859-1931)There they go marching all in step so gay!

Smooth-cheeked and golden, food for shells and guns.

Blithely they go as to a wedding day,

The mothers’ sons.The drab street stares to see them row on row

On the high tram-tops, singing like the lark.

Too careless-gay for courage, singing they go

Into the dark.With tin whistles, mouth-organs, any noise,

They pipe the way to glory and the grave;

Foolish and young, the gay and golden boys

Love cannot save.High heart! High courage! The poor girls they kissed

Run with them: they shall kiss no more, alas!

Out of the mist they stepped-into the mist

Singing they pass.

It’s unclear whether in England she lost her Irish nationalism. She clearly stopped seeing England as an enemy: “affection for England and love of Ireland could quite well go hand in hand.” The couple moved back to Ireland in 1911 after Henry was appointed resident magistrate for Castlebar, Co. Mayo. Per Irish Biography, she didn’t like the “radical climate” she found on her return. The 1916 Easter Rising, a rallying event in the minds of nationalists, was to her, “rebellion.”

Tynan had four sons and a daughter. Two of the boys died in infancy. The surviving two sons went on to fight for England in World War I. It’s not surprising that she’d soften towards a nation her sons tied their fortunes to. I have access to what of her poetry can be scraped from the internet and an excoriable 2014 electronic edition of fifty or so poems horridly formatted by whoever had the good sense not to attach their name to as editor (I want my $2.40 back.) It’s a limited sampling, but there’s a noticeable turn. From the beginning of the war she writes about soldiers, their mothers, the world wracked by war, and lost souls. The pot-boilers go on, but poetry, again from my limited sampling, is her sink.

Quiet Eyes

The boys come home, come home from war,

With quiet eyes for quiet things

A child, a lamb, a flower, a star,

A bird that softly sings.Young faces war-worn and deep-lined,

The satin smoothness past recall;

Yet out of sight is out of mind

For the worst wrong of all.As nightmare dreams that pass with sleep,

The horror and grief intolerable.

The unremembering young eyes keep

Their innocence. All is well!The worldling’s eyes are dusty dim,

The eyes of sin are weary and cold,

The fighting boy brings home with him

The unsullied eyes of old.The war has furrowed the young face.

Oh, there’s no all-heal, no wound-wort!

The soul looks from its hidden place

Unharmed, unflawed, unhurt.

Her daughter Pamela became a novelist. Her son Giles was a correspondent for The Times in Buenos Aires and Santiago according to Wikipedia. I didn’t find any information (I’m certain it’s available but not about to read her five volume autobiography) about the other son Theobold, other than that he survived the war. Of her husband’s 1919 death, she wrote it “had come to me at the end of the War as though the immunity of the boys had been bought with their father’s life.” I don’t know who Percy, mentioned in the below poem, was. If her intent was to evoke a mother’s feeling for all the war dead, she did well enough to send me scouring high and wide for the names of her children, certain that one must be named Percy.

A Lament

(For Holy Cross Day, 1914)Clouds is under clouds and rain

For there will not come again

Two, the beloved sire and son

Whom all gifts were rained upon.Kindness is all done, alas,

Courtesy and grace must pass,

Beauty, wit and charm lie dead,

Love no more may wreathe the head.Now the branch that waved so high

No wind tosses to the sky;

There’s no flowering time to come,

No sweet leafage and no bloom.Percy, golden-hearted boy,

In the heyday of his joy

Left his new-made bride and chose

The steep way that Honour goes.Took for his the deathless song

Of the love that knows no wrong:

Could I love thee, dear, so true

Were not Honour more than you?(Oh, forgive, dear Lovelace, laid

In this mean Procrustean bed!)

Dear, I love thee best of all

When I go, at England’s call.In our magnificent sky aglow

How shall we this Percy know

Where he shines among the suns

And the planets and the moons?Percy died for England, why,

Here’s a sign to know him by!

There’s one dear and fixèd star,

There’s a youngling never far.Percy and his father keep

The old loved companionship,

And shine downward in one ray

Where at Clouds they wait for day.

[This entry is cross posted at ordinary-times.com]