POETS Day! Emily Brontë

I was of the assumption that all women read Emily Brontë as girls. I never had cause to question.

I have an uncle who is never bored. He’s always up to or up for something. One of the collateral benefits of restlessness is that he banks interesting places and activities he discovers wandering around. There’s rarely a “What do you want to do?” because he’s got a backlog of interesting half-explored outings nipping at his synapses.

He found a used book store in Fredrick, Maryland he says has more than its share of signed books. I bought signed copies of William F. Buckley’s The Unmaking of a Mayor and Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits (“Happy Birthday Frieda! Here’s a Useless Book!”) My uncle’s pretty sure there’s a bored or impish clerk with a sharpie, but I choose to believe otherwise.

Another time we went to NRA headquarters, but only partially to shoot. The night before, he told me about the strict protocols and double gun safe lock check ID frisk metal detector side eye you get when going in because they know more than any mass attrocity, an incident at the NRA home base would be the PR nightmare. We sat in the parking deck after we were done, guns locked and trunked, and riffed that despite all the guns in proximity, this place is a mugger’s dream of unarmed targets wandering around in the dark.

He’s always coming up with stupid, giggly fun like that.

Happy POETS Day! Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday. There’s something off or silly in your town waiting to be found. Take a few hours away from work and make fun. Go do that.

First, verse.

***

I was of the assumption that all women read Emily Brontë as girls. The soon-to-be menfolk would retire to the parlour mad they aren’t yet old enough for brandy and cigars and read Treasure Island, Mark Twain, and Ivanhoe while the women retired to have pillow fights and to read Jane Austen and a Brontë or three wherever they went when the men were in the parlour. I never had cause to question.

There’s a movie adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights coming out soon and I’m a boy, so I was going to ask my wife if the story is any good and would it be worth seeing. First, I mentioned that I read a couple of her poems in the Oxford Book of English Verse and then asked about the movie.

“I’ve never read any of the Brontës,” she said. I told her about my parlour assumption.

“I never did. I thought Charlotte wrote Wuthering Heights, but I guess I was thinking of Jane Eyre. I read that.”

“So you have read the Brontës.”

“Not really. Just Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, but like I said, I thought Charlotte wrote it. I’ve never read any of their poetry. I’m pretty sure I didn’t and if I did I don’t remember it. I don’t think I even knew they wrote poetry. I definitely never read Anne.”

At the time I couldn’t name another book by the Brontës other than Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights and neither could my wife, so by “never,” she meant all of the ones she could think of. She says the pillow fight thing doesn’t happen.

Not many read Emily Brontë’s, or any of the Brontës,’ poetry while she was alive; a short window, but still. Her older sister Charlotte found Emily’s poems and got angry because her sister kept them private, an apparent betrayal of the creative spirit of the house. She convinced Emily and the youngest, Anne, to collaborate on a collection of poetry. To be taken seriously as authors, the girls adopted male pen names. Each took a first name beginning with the letter corresponding to the one beginning their own and added the surname Bell, so Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë became Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.

I don’t know if I can say that Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell was well received. There were three reviews, all positive, though all anonymous [hmmm…], and all singled out Emily for specific praise. In the critical sense it was, but the book only sold two copies. It was barely received at all. (Wikipedia notes that the sisters were very pleased nonetheless because one of the two buyers requested autographs.)

Stanzas

Emily Brontë (1818-1848)I’ll not weep that thou art going to leave me,

There’s nothing lovely here;

And doubly will the dark world grieve me,

While thy heart suffers there.I’ll not weep, because the summer’s glory

Must always end in gloom;

And, follow out the happiest story—

It closes with a tomb!And I am weary of the anguish

Increasing winters bear;

Weary to watch the spirit languish

Through years of dead despair.So, if a tear, when thou art dying,

Should haply fall from me,

It is but that my soul is sighing,

To go and rest with thee.

It’s not a bad poem. It’s a little predictable and easily categorized, lost in a pile of Victorian despair (though there’s possibly a little more to consider here which I’ll get to in a moment.) The flow is pleasant and there’s a little wordplay. Generally when I see a poem titled “Stanzas,” which is often enough, I assume it’s untitled and often make a presumption that it is unfinished or unpublished during the author’s lifetime.

There is another poem, this one available in the very posthumous The Complete Poems of Emily Jane Brontë (1941), called “Stanza,” not plural. I was not expecting to like it as much as I do. Where “Stanzas” is not bad, “Stanza” is particularly good.

“Back returning” should be redundant, but it works when you give a moment and realize what she’s saying. The perceived disruption lends a stream of consciousness feel to the first stanza, a pace that’s broken quickly by end of line pauses and stops that carry through the rest.

Stanza

Often rebuked, yet always back returning

To those first feelings that were born with me,

And leaving busy chase of wealth and learning

For idle dreams of things which connot be:To-day I will seek not the shadowy region;

Its unsustaining vastness waxes drear;

And visions rising, legion after legion,

Bring the unreal world too strangely near.I’ll walk, but not in old heroic traces,

And not in paths of high morality,

And not among the half-distinguish’d faces,

The clouded forms of long-past history.I’ll walk where my own nature would be leading:

It vexes me to choose another guide:

Where the grey flocks in ferny glens are feeding,

Where the wild wind blows on the mountain side.

In her article “Robert Frost: ‘The Road Not Taken,’” Katherine Robinson writes,

“Soon after writing [“The Road Not Taken”] in 1915, Frost griped to Thomas that he had read the poem to an audience of college students and that it had been ‘taken pretty seriously … despite doing my best to make it obvious by my manner that I was fooling. … Mea culpa.’”

According to her, the poem was written as a jibe towards his friend Edward Thomas whose frustrating indecisiveness spoiled their frequent walks together though he later leaned into the larger meaning others assumed. “Stanza” seems the cousin of that individualist notion associated with Frost’s poem.

Brontë (Emily from now on unless indicated) was an oddball. She was shy and withdrawn, a homebody, brilliant in the eyes of more than one teacher, quick to anger, and violent. Much of what we know of her we get from Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte, and that as told to Gaskell by Charlotte, who held her sister in awe. She mythologizes Brontë, to what degree is hard to say.

In an 1850 volume containing Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, Charlotte wrote of Emily,

“Under an unsophisticated culture, inartificial tastes, and an unpretending outside, lay a secret power and fire that might have informed the brain and kindled the veins of a hero; but she had no worldly wisdom; her powers were unadapted to the practical business of life. An interpreter ought always to have stood between her and the world.”

and,

“My sister’s disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favoured and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of home. Though her feeling for the people round was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced. And yet she knew them: knew their ways, their language, their family histories; she could hear of them with interest, and talk of them with detail, minute, graphic, and accurate; but WITH them, she rarely exchanged a word.”

We’d hope to glean something of Emily from her poetry, but that discovery is frustrated. The sisters, primarily Emily and Anne, had a shared fantasy world called Gondal. There is Angria as well, but as far as I can tell Angria is a rival to Gondal within the Gondal universe. All of those stories are lost, but we know a great deal of Emily’s poetry was meant for the Gondal stories, spoken by the Gondal characters with a variety of personalities. Some argue all of her poetry is from her fantasy stories. We have no idea who the persona of any is. With that in mind, “Stanzas” above, which I called Victorian despair, may be lament of an enchanted umbrella pining for summer rains, for all I know. She’d occasionally take a break from writing about poetry or her fantasy worlds. An interesting reading of “Stanzas” puts the persona as her imaginary world or poetic impulse saying goodbye for a bit.

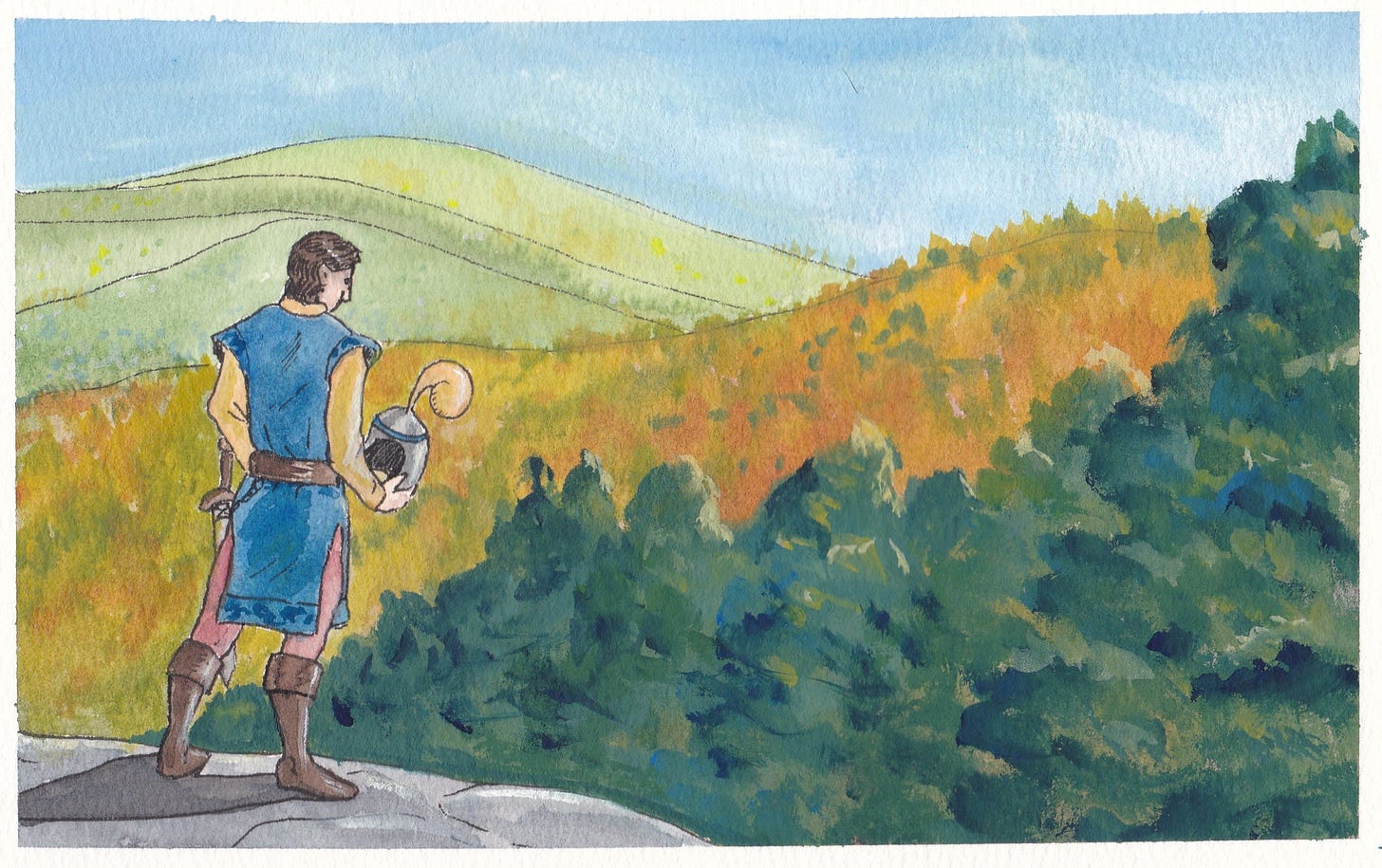

Some personas from Gondal are easy to spot. At least I assume this next is from her stories. He seems like a noble questing type you’d want lying about your fantasy world’s local Inn, minding his own but ready to embroil an orphan (with no idea he’s of royal blood) in an adventure if pressed by circumstance.

The Old Stoic

Riches I hold in light esteem,

And Love I laugh to scorn;

And lust of fame was but a dream

That vanish’d with the morn:And if I pray, the only prayer

That moves my lips for me

Is, ‘Leave the heart that now I bear,

And give me liberty!’Yes, as my swift days near their goal,

‘Tis all that I implore:

In life and death a chainless soul,

With courage to endure.

In an addition to a later edition of Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell titled “Selection from the Literary Remains of Ellis and Acton Bell By Currer Bell,” Charlotte wrote of this next poem, “The following are the last lines my sister Emily ever wrote:—” Not everyone believes that. Either way, noble defiance in the face of eternity serves Charlotte’s mythologizing project. As to last known spoken words, Emily’s were, “If you will send for a doctor, I will see him now.” That was days after she said “no poisoning doctor” in the midst of a tubercular turn. Charlotte wrote,

“She grows daily weaker. The physician’s opinion was expressed too obscurely to be of use – he sent some medicine which she would not take. Moments so dark as these I have never known – I pray for God’s support to us all.”

She died a few hours after consenting.

The poem is untitled in Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. I’ve seen it most often refered to by the first line, “No coward soul is mine,” but it’s “Last Lines” in the Quiller-Couch Oxford Book of English Verse. I like Quiller-Couch.

Last Lines

No coward soul is mine

No trembler in the world’s storm-troubled sphere

I see Heaven’s glories shine

And Faith shines equal arming me from FearO God within my breast

Almighty ever-present Deity

Life, that in me hast rest,

As I Undying Life, have power in TheeVain are the thousand creeds

That move men’s hearts, unutterably vain,

Worthless as withered weeds

Or idlest froth amid the boundless mainTo waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by thy infinity,

So surely anchored on

The steadfast rock of Immortality.With wide-embracing love

Thy spirit animates eternal years

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates and rearsThough earth and moon were gone

And suns and universes ceased to be

And Thou wert left alone

Every Existence would exist in theeThere is not room for Death

Nor atom that his might could render void

Since thou art Being and Breath

And what thou art may never be destroyed.

[This entry is cross posted at ordinary-times.com]