POETS Day! Edwin Muir’s “The Horses”

Eliot writes that Muir was not concerned with technique, “He was first and formost deeply concerned with what he had to say.”

Mississippi is where I pass on the right. Folks come from all round to make me pass them on the right in Mississippi. I saw tags from New York, and I passed them on the right in Mississippi. I saw tags from North Carolina driving 70 mph, and I passed them on the right in Mississippi. Someone driving in car with tags from neighboring Arkansas, seeing me pass him on the right in Mississippi, so loved being passed on the right in Mississippi that he let a whole train of fellow travelers dart past a slow truck in the right lane and pull up behind him before changing lanes to pass him on the right in Mississippi and then change lanes back again to pass a pick-up towing an empty trailer in the right lane some medium distance ahead. We all snaked.

I will never understand Mississippi. I read a Joan Didion novel in Louisiana. It was very good.

It’s POETS Day so Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday. Get out of work mid afternoon. Live life in the fast lane (but actually drive fast.)

First, a little verse.

***

Edwin Muir published the piece of literary criticism, Scott and Scotland, in 1938. In it he argues if Scotland is to have a national literature, they must do away with far and wide dialects and decide on a common language.

“If Shakespeare had written in the dialect of Warwickshire, Spenser in Cockney, Ralegh in the broad Western English speech which he used, the future of English literature must have been very different, for it would have lacked a common language where all the thoughts and feelings of the English people could come together, add lustre to one another, and serve as a standard for one another.”

Glasgow sneered incomprehensibly, Edinburgh twanged nasally, and Aberdeen wore fuzzy boots.* The one language common to them all through radio, newspaper, and all the missives of empire, was English. He put it that Scots survived in nursery rhymes and “anonymous folk-song.” The old language as men lived in his time “expresses therefore only a fragment of the Scottish mind.” He made the case that the Scots, who already spoke English, needed to proceed in English in their literature. This made him very unpopular with Hugh MacDiarmid (M’Diarmid), whose “Lallan” movement, “Lallan” being a Scots pronunciation of “Lowlands,” was beating the curtains for kilts and cursing. Muir had no patience for nationalism.

Scott and Scotland earned him few friends and it doesn’t seem like many pounds. I can’t say that he won the argument. MacDiarmid clearly lost, though how much Muir had to do with the outcome, I can’t say. My after-the-battle sympathies are strongly with Muir, for whatever that’s worth. Imagine a world where Scots of note persisted in Lallan or other impenetrable dialects. I’ll take on faith and sales numbers that translations of Muriel Spark are worth reading, but I can’t imagine her wit and weird come across fully via an intermediary. She’d be diminished for the non-Scot reader like me. I like the crime novels by Ian Rankin so much I named my dog Rebus, after his stubborn but endearing detective character. Would Rankin have reached America if he’d written in niche dialect instead of the King’s English as God and Longshanks intended? My dog would be named after some less self destructive detective; Nero, which is actually pretty good, or Poirot, which, to borrow from P.J. O’Rourke, would be embarrassing in a duck blind. I feel like I owe Muir some thanks for fighting the good fight.

He grew up in what was ostensibly late 19th Century Orkney which, shielded by mountains and not yet a cutesy filming location bringing filming types and their make up artists, was safely afield of cultural forces and avoided the social upheavals of the Industrial Revolution. Robert Richman writes, in “Edwin Muir’s journey” (The New Criterion, April 1997):

“Orkney natives were ignorant of modernity and its discontents. ‘The farmers did not know ambition and the petty torments of ambition,’ Muir noted, nor did they ‘know what competition was, though they lived at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign; they helped one another with their work when help was required, following the old usage; they had a culture made up of legend, folk-song, and the poetry and prose of the Bible.’”

In 1901, his parents moved the family from the islands to Glasgow when Orkney rent increases made tenement farming too costly. Muir was fourteen at the time of the move. By his eighteenth birthday, both of his parents and two of his six siblings were dead. Per Richman, his father “collapsed and died.” A brain tumor claimed one brother, consumption another. His mom “died.” I don’t know from what.

He worked a series of menial jobs. At one point, and this seems too metaphorically on point so I’m asking for a little trust in repeating it, he worked as a clerk in a bone factory, where bones were turned into charcoal; the Orkney child of nature exiled to a mechanized Tartarus where he wrought from living remains through some damned alchemy the fuel to power Ur-Mordor. In the preface to Muir’s posthumous Collected Poems, T.S. Eliot wrote, “There is the sensibility of the remote islander, the boy from a simple primitive offshore community who then was plunged into the sordid horror of industrialism in Glasgow.”

Finally, he met Willa Anderson, married her in 1919, and moved to London and later beyond. They lived happily ever after. Honestly.

With Willa, Muir translated many influential German works. Most notably, they introduced Franz Kafka to the English speaking world. Per Wikipedia, “Willa recorded in her journal that ‘It was ME’ and that Edwin “only helped.”

The two got about. They lived in various places on the Continent—Wikipedia lists Dresden, Vienna, Rome, Salzburg, and Prague—moved briefly back to Scotland (St. Andrews and Midlothian, not Glasgow), Boston, and Cambridge. He taught, worked briefly for the British Council, reported, translated, and wrote literary criticism to pay bills, and wrote novels briefly. For reasons I’m unaware of, Muir stopped writing poetry after a promising start and didn’t take it up again until his mid-thirties. All I know is that he regretted the break.

Some sources laud Muir’s The Story and the Fable: An Autobiography (1940) and An Autobiography (1954) while others find them incomplete. From what I’ve read, they’re middling as autobiographies but are revelatory as companion works to his poetry. He obsessed about time and imagination, how we can never go back to the past except in the completeness of imagination, that imagination alters the past, that imagination is its own realm, different from but tangled in reality. He was enamored of mythology and regeneration myths, the idea that we are all living our own version of a repeating cycle, that we’ve all been here before.

Muir felt out of place. He was ripped from his ideal place at a young age, re-imagined it better than it already could have been, and pined. From his journal:

“I was born before the Industrial Revolution, and am now about two hundred years old. But I have skipped about a hundred and fifty of them. I was really born in 1737, and till I was fourteen no time-accidents happened to me. Then in 1751 I set out from Orkney for Glasgow. When I arrived I found that it was not 1751, but 1901, and that a hundred and fifty years had been burned up in my two days’ journey. But I myself was still in 1751, and remained there for a long time. All my life since I have been trying to overhaul that invisible leeway.”

Eliot writes that Muir was not concerned with technique, “He was first and formost deeply concerned with what he had to say,” that he found, “the right, the inevitable way of saying what he wanted to say.” Muir himself was dismissive of New Criticism specifically and didn’t align with any school. He wrote with clarity and directness to convey the ideas that captured his thinking.

Below is one of his most famous poems, “The Horses,” a return to simplicity after the conclusion of advancement. Eliot called it, “that terrifying poem of the ‘atomic age.’”

The Horses

Edwin Muir (1887-1595)Barely a twelvemonth after

The seven days war that put the world to sleep,

Late in the evening the strange horses came.

By then we had made our covenant with silence,

But in the first few days it was so still

We listened to our breathing and were afraid.

On the second day

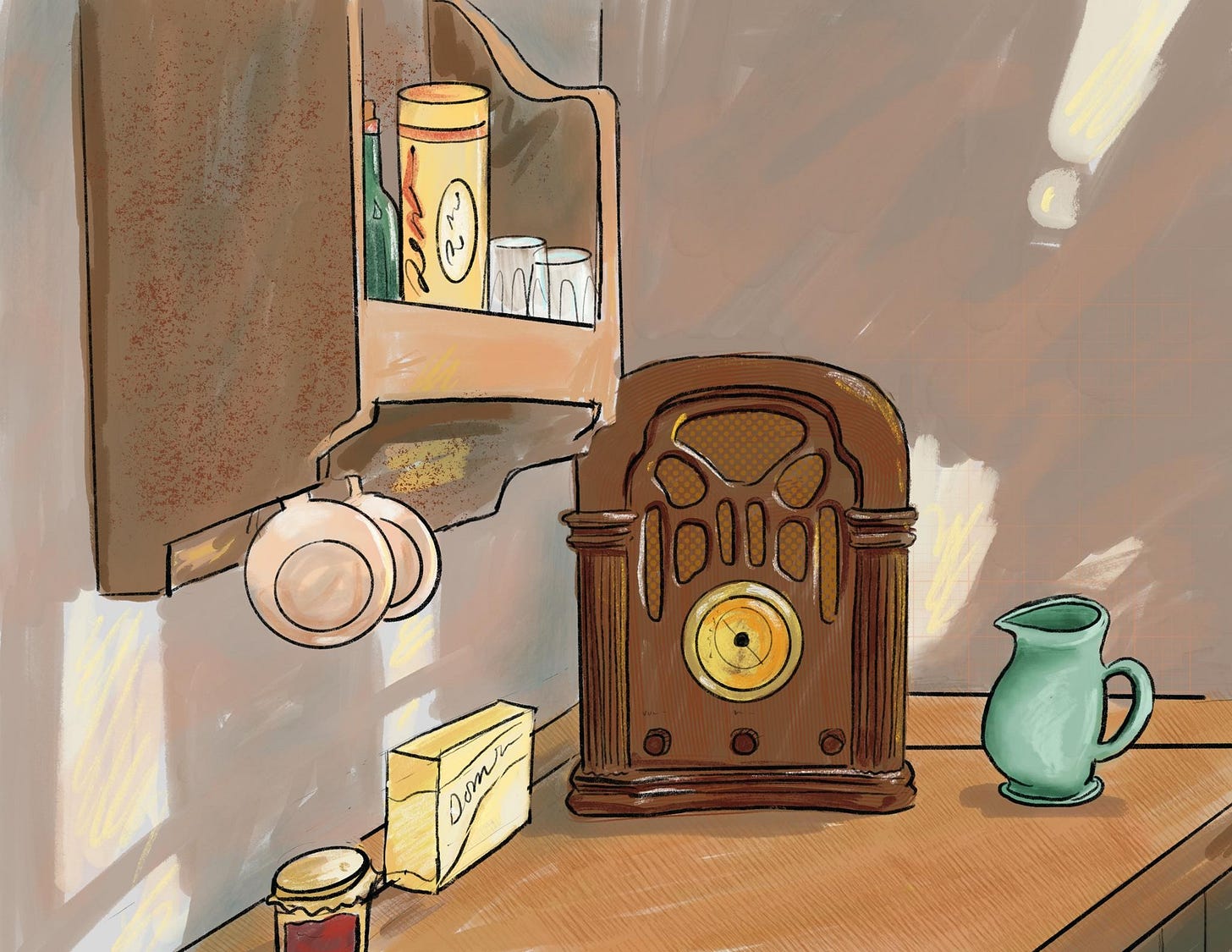

The radios failed; we turned the knobs; no answer.

On the third day a warship passed us, heading north,

Dead bodies piled on the deck. On the sixth day

A plane plunged over us into the sea. Thereafter

Nothing. The radios dumb;

And still they stand in corners of our kitchens,

And stand, perhaps, turned on, in a million rooms

All over the world. But now if they should speak,

If on a sudden they should speak again,

If on the stroke of noon a voice should speak,

We would not listen, we would not let it bring

That old bad world that swallowed its children quick

At one great gulp. We would not have it again.

Sometimes we think of the nations lying asleep,

Curled blindly in impenetrable sorrow,

And then the thought confounds us with its strangeness.

The tractors lie about our fields; at evening

They look like dank sea-monsters couched and waiting.

We leave them where they are and let them rust:

“They’ll molder away and be like other loam.”

We make our oxen drag our rusty plows,

Long laid aside. We have gone back

Far past our fathers’ land.And then, that evening

Late in the summer the strange horses came.

We heard a distant tapping on the road,

A deepening drumming; it stopped, went on again

And at the corner changed to hollow thunder.

We saw the heads

Like a wild wave charging and were afraid.

We had sold our horses in our fathers’ time

To buy new tractors. Now they were strange to us

As fabulous steeds set on an ancient shield

Or illustrations in a book of knights.

We did not dare go near them. Yet they waited,

Stubborn and shy, as if they had been sent

By an old command to find our whereabouts

And that long-lost archaic companionship.

In the first moment we had never a thought

That they were creatures to be owned and used.

Among them were some half-a-dozen colts

Dropped in some wilderness of the broken world,

Yet new as if they had come from their own Eden.

Since then they have pulled our plows and borne our loads,

But that free servitude still can pierce our hearts.

Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.

*“Fuzzy Boots” was slang for Aberdeenians/Donian/Aberdeenbingians when my wife lived in Edinburgh in the 90s. Their colloquial meeting version of “Where are you from?” was “From where are you about?”, which, in sludge thick Aberdeenoise, sounded to outsiders like “Fuzzy boots?” And then they’d all fight.